Making Better Anki Flashcards: Principles For High-Yield Cards.

In this post, you’re going to learn the most important principles I learned from experience that will help you create high-quality, memorable flashcards you can use in the long-term.

Quite frankly, most flashcard tips on Google just plain suck.

Many are just piecemeal “hacks” that don’t apply to other situations.

With the principles I’m going to show you, on the other hand, you will be able to apply them no matter what you’re learning.

In addition, you’re also going to learn the anatomy of a high-quality flashcard in the latter parts.

Other than that I’ve made a quick summary of the most common mistakes I saw in my cards and from the experiences of other AnkiHeads and Knowledge workers on the Internet, you can read about that here.

[Note: DO NOT SKIM THE DAMN ARTICLE— not even this guide. You’re going to lose out on a LOT of the nuances I’ve shared.]

Anyway, creating better flashcards doesn’t mean you’re going to use a ton of add-ons and card types or styles. Why? Because they’re supplementary at best.

What you want is the vital few that brings MOST of the results.

After you learn the principles I’ve laid out here, as well as read the guide on common mistakes I linked to you just now, you’ll already have the most important stuff out there regarding “creating better flashcards.”

They simply dwarf all other “tips” when you sort them out by importance.

All that’s left is practice.

That should save you a lot of time, shouldn’t it?

And talking about “saving time” — let’s just address one thing first.

Does Making Anki Flashcards Really “Take Too Long”?

Many Anki newbies (and most people) often try to put image occlusion masks on their lecture slides to make things easier NOW, but fail future exams because they can’t comprehend the higher level concepts the exams require.

They approach their studying in what I call a Time Debt mindset — they try to “study faster”, even if it costs them a lot of time in the future.

Specifically, they “study more efficiently” but in the end, they create much bigger time wasters. I talk about it in my Using Anki Efficiently mini-Guide, but essentially, these time-wasters are:

- Getting blanked out because your cards are too vague

- Having to re-learn a prerequisite material you’ve already studied before

- Re-taking a course because you failed to remember stuff when it matters most; and worst of all,

- Not graduating in time

Patrick McKenzie, a programmer who runs 4 software businesses, articulates it better:

Most people think, intuitively, time always rots. You get 24 hours today. Use them or lose them. The foundation of most time management advice is about squeezing more and more out of your allotted 24 hours, which has sharply diminishing returns.

In contrast, when you adopt a Time Asset mindset, you end up doing what needs to be done NOW — even if it initially takes more time — because that will save you a LOT more time in the future.

Thus, the more thought you initially spend into creating a flashcard, the longer it remains useful and the more rewards you’ll be able to reap from it. (Translation: You avoid wasting time in the long run)

As James Clear says:

Each Time Asset that you create is a system that goes to work for you day in and day out. […] If your schedule is filled with Time Debts, then it doesn’t matter how hard you work. Your choices will constantly put you in a productivity hole. However, if you strategically build Time Assets day after day, then you multiply your time exponentially.

So how do better flashcards help you save more time?

By eliminating the much bigger causes of waste:

- The time you’re stuck answering incredibly vague cards

- The time spent in having to re-learn a prerequisite material because you “life hack’ed” your way to memorizing lecture slides; or, probably the worst,

- The time spent re-taking a big exam just because you failed to remember important knowledge until the end

But before I tell you “how”, it’s important for you to learn the thinking behind this first.

I want you to think of flashcards like “seeds”. They’re “idea seeds” that eventually grow and root themselves deep in your brain. They give high-quality “harvests” when you tend to them each day.

Problem is, bad seeds always turn into bad plants. Put plenty of them in your land and, without you noticing, more hard work will yield more of these bad harvests.

This is why investing time into creating atomic, future-proof flashcards created from holistic learning is so important. (More later)

By the end of this lesson, you’ll learn how to plant only the “good seeds” in your memory farm.

On top of that, what you’re going to learn here are evergreen PRINCIPLES extracted from YEARS of combined experience and hour upon hour of testing.

Best of all, you’ll be able to use these for YEARS, too — because principles never change.

So I urge you to take notes on these. Open up a New Note in Evernote, a notepad app, or just get a pen and paper and take some good notes you can refer to again and again.

Why? Because at some point — who knows — these articles might be gone. I’m not running ads, you see.

But let me warn you before you continue:

Please please please don’t expect you’ll be able to internalize them after 3 minutes if you’re just going to skim these.

That’s because it will take you a lot of WORK to practice these principles yourself and get them right the first time.

3 Principles for Effective Flashcards

Think about these 3 principles as “rules” for developing your Anki skills.

As you apply these principles for the first time, you should expect that it’d take you a long time. But of course, as you practice them, you’ll get faster and faster. By then, your Anki skills have developed.

So remember these principles — when you do, you’ll already be ahead of 99% of Anki users with Time Debt mindsets.

Principle 1. Atomic

Atomic means (ideally) cueing one idea per card, usually done in two ways:

- Increased specificity. Breaking a complex idea down to multiple specific ones and creating cards for each. (easiest)

- Increased integration. Condensing multiple ideas into a single, higher-level idea. (hardest — needs synthesis and pattern recognition)

The primary purpose of this is to avoid what psychologists call cue overload.

Psychologists explain that when you use cues that have more than one associated memory, it tends to impede recall rather than help it. Your cue, then, becomes almost useless to help you recall a specific detail.

To demonstrate, if I asked you, “What are the white-colored items in your bedroom?” as compared to “think of white-colored objects”…

…then you’ll be able to answer the former in less time because there’s more cue overload in the latter.

Side Note: This is also why I don’t recommend using Anki for lists greater than 4 items, unless:

- They’re highly related to each other; or

- Can be remembered with a single mnemonic __ Just use memory techniques rather than Cloze Overlapper. They’re way faster and more robust.

Anyway, as a side benefit, Nielsen says:

…one real benefit is that later I often find those atomic ideas can be put together in ways I didn’t initially anticipate. And that’s well worth the trouble.

Not only are you able to review atomic flashcards faster, but you’ll also be able to avoid domain dependent thinking. (ex: when Physics knowledge gets stuck only in Physics subjects)

Long story short, vague questions suck.

Go atomic.

Both of these tie in perfectly to the next point…

Principle 2. Holistic

Holistic means associating/integrating an idea into your existing knowledge first before putting it into Anki.

While “holistic” might sound like a contradiction to the first one, there is a profound distinction at work here:

Have holistic ideas, but atomic flashcards.

Why is this so powerful? Because:

- The more you use an old idea to understand new ones, the easier it gets to recall the old one.

- The more associations an idea has, the better you’ll remember it.

- Simplifying multiple complex ideas into simpler structures allow for better information encoding.

Three ways to guarantee you’re creating holistic cards are:

- Encoding ideas before you create flashcards. Many people make the mistake of using shared decks for conceptual subjects. It’s probably fine for isolated information, but then again, encoded information is far easier to recall than isolated ones.

- Adding pseudocontext. These are “fake context” that help you remember an idea while not necessarily building higher-level ideas on top of it. It’s the weakest one, but it’s quite useful for combatting interference. For example, when you’re trying to remember “Sternocleidomastoid” and you remember “Son Goku” when you see it, then put that association when you’re testing your cards! It makes formulation a bit fun, actually.

- Adding visuals. Self-explanatory, but you can see more examples when you get to the “Anatomy of a Good Card” section down below.

Principle 3. Future-Proof

Why should you future-proof your cards?

Well, if you’re using Spaced Repetition — a long-term process — then it’s only logical that your cards must also be usable in the long-term.

Besides, you’re NEVER the same person as you were in the past. You’re constantly growing. Your beliefs change. Your influences shift.

So when you think about it, won’t it just be the same for your future self? Isn’t it safe to say that you’d become a different person in the future, too?

Well, the problem is many people don’t realize this. It’s not their fault, tho.

Psychologists have found we have a tendency to believe that vividly knowing something now would automatically lead to remembering the same thing — with the same level of detail — in the future.

They call this the stability bias.

Just imagine the hundreds of times you’ve nodded your head in a well-explained lecture and then forgetting everything come exam day.

Or looking at your notes you took just last year just to figure out that you can’t understand any of it anymore.

You probably went from “Yeah, I’m gonna remember that…” to “Who wrote this damn thing?”

That’s stability bias in a nutshell.

Two ways to do this:

- Add more specifiers

- Create more context

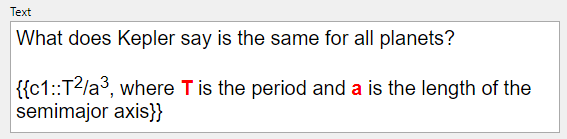

Just take a look at this question:

“What does Kepler say”? Yes, it’s atomic and quite holistic, but do you think you’d still understand this question after, say, a month?

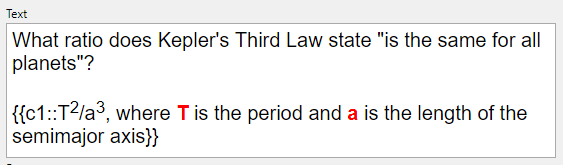

Compare this to the revised, future-proof question:

By stating the “ratio” and “Kepler’s Third Law,” [SPECIFIER + CONTEXT, respectively] I’ve immediately created the shortest path between the cue and the memory.

Why is this so powerful? Because it allows you to answer quickly — no matter how many days ago you’ve created the same card.

Then again, I’m assuming that you follow the other two rules, too.

In sum, these 3 principles are what make a good card good.

However, these wouldn’t matter if you can’t apply them. Which is why you need to learn what “good card anatomy” looks like.

Let’s talk about that next.

The Anatomy of a Good Anki Card

Having used a ton of flashcards as well as having re-created a couple of decks, I can say that there’s a repeatable process for creating an extremely well-crafted card.

Before that, though, let’s talk about card types.

There are only three card types that matter — you can do any variation of question and answers using these card types alone.

- Basic. Basic cards are best for bulk uploads and the straightforward question-answer pair. Perhaps it’s the most convenient card type if you want to create hundreds of cards at once. But you won’t be doing that a lot, so I won’t cover it here.

- Cloze Deletion. Cloze can create the same questions as a basic card type, but you can do “fill-in-the-blanks” stuff here. However, I don’t recommend that for two reasons: 1) It makes it easy to fall for the collector’s fallacy where you collect cards you don’t “own”. 2) I found that “fill-in-the-blanks” type of prompts train you to complete a statement rather than to commit what you’ve learned into memory. I’m not saying you shouldn’t do it at all, but rather you should do it conservatively.

- Image Occlusion. This is just Cloze deletion applied to images. Of course, you might ask, “If fill-in-the-blanks style doesn’t work for learning, then is it the same for image occlusion?” Not necessarily. Visuals are far more memorable than words — it beats all senses combined. (Here is a humongous set of references to prove that.) Images can stand on their own — it’s kinda weird, but it’s like images already have “context” built-in.

Use either one of Basic and Cloze, in addition to Image Occlusion, and you already have everything you need. Seriously.

Virtually all types of questions can be made with those three.

Others are just variations that suit more specific uses (Vocabulary, for example.) but in no way the 3 basic types can’t do the same thing.

As for the add-ons, you only need 3 as well. Here they are.

- Image occlusion. Of course, I wouldn’t be telling this card type if you wouldn’t install it. (duh, Al) I bet you have this one already — it’s pretty popular. In case you don’t, here’s the link. Even if you’re a heavy reader, sometimes you’ll find custom visuals with labels help you recall in a more efficient way than words. That is the perfect time to use it.

- Review heatmap. Back then, I believed these heatmaps only served as “motivators” because of the visibility of progress. But it’s actually for a bigger purpose — it gives you objective feedback of your study habits. Feelings are unreliable — they fluctuate, and we can’t predict nor remember feelings accurately — but numbers don’t lie.

- When you fall off track, you’ll immediately know. When you’re not adding new cards per day, you’ll immediately know. Review heatmaps drastically decrease the delay of your feedback loop — making your learning system more “stable” i.e. less likely to fluctuate.

- Hierarchical tags. I told you not to use topics as decks in a previous lesson, and this is another reason why. If decks are huge umbrellas, then tags are the smaller “sub-umbrellas”. They don’t really separate what you can review, but tags organize them very well and prove to be extremely helpful for custom study sessions.

Surely, there are other add-ons, but the majority of them aren’t essential. They’re supplementary at best, and only provide miniscule benefits.

We’re trying to stay as lean as possible here so you can focus on what matters — creating high quality cards. (We literally just talked about that…)

Now then, if card quality is defined by the principles, and the cards differ in types, then the card’s anatomy puts the two together.

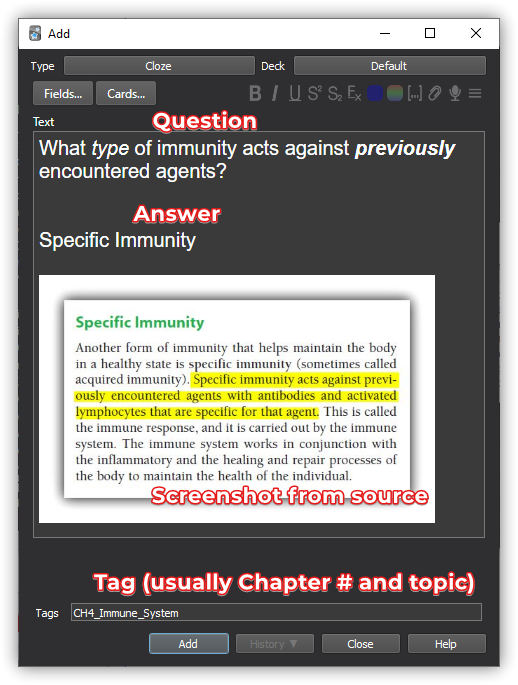

For your convenience, this is what we’ve previously discussed in the first lesson:

The Ultra-specific question & The Answer

Just to be clear, statements aren’t questions.

It’s literally a huge tendency for Anki beginners to copy their notes into Anki and then treat them like an identification-type exam.

They literally turn their notes into cards.

It might work, but upon closer examination, you’ll realize it doesn’t test understanding — but rather it merely tests your ability to complete the missing pieces.

Questions allow you to test your understanding of concepts — not to mention they’re more natural to deal with.

Answers are self-explanatory.

But again, make sure it’s not a list greater than 4 items. (The number was based on working memory slots, FYI.) If you’re going to do that, make sure you use either the Cloze Overlapper or Memory Techniques.

I prefer memory techniques because then I can create meta-mnemonic cards (a card that helps you remember your mnemonics) to remember them better.

The Excerpt

I got this one from Prerak Juthani back in 2020.

Essentially, you’d want to put a screenshot/excerpt of the material you got your card from.

That way, you won’t have to go back to the material itself to relearn the card in case of a total lapse — there’s the context embedded in an excerpt, after all.

(Obviously you won’t need these in Image Occlusion.)

You can say it’s also a future-proofing element.

The best part?

This allows you to totally ditch notebooks (eventually) and go straight to Anki to revise.

Prerak Juthani is living proof — he’s totally paperless when studying. However, if your use case is to develop ideas or enrich your knowledge, then ditching notes is quite debatable.

Just to be clear, I’m not telling you to ditch notebooks — it’s just one of the luxuries Anki can offer.

Conclusion: Creating Better Flashcards Is Just The First Step

Look, if you think creating flashcards will still take you a lot of time even after reading this guide and the most common mistakes made while making Flashcards, then I have a very special treat for you — we’ll get to it in a moment.

At this point, you should already have a basic idea of how you should approach flashcard formulation. And, with the principles you’ve learned including the anatomy of a good Anki flashcard, you should be able to think of the “tactics” for yourself.

All that’s left now is to turn this knowledge into action.

Quite frankly, you will NOT get better just by knowing about these stuff.

Michael Phelps didn’t watch swimmers or tried to “learn new swimming tricks” to become Michael Phelps.

He deliberately practiced the skill day in, day out.

So you need to practice.

That’s the hard truth about skills.

Good news is, this is a skill worth having. You can learn it once, and use it forever.

In any case, I’m assuming that you wanted to create better flashcards because you want to remember information better AND spend less time studying.

Okay, sure, formulation skills help a lot — but only up to a certain point. There are other more important constraints to worry about after that.

Specifically, you’ll find that in the “big picture” of learning.

How Anki fits into the bigger learning process.

Why is this important? Because if you’re not working with how your brain stores information, then no amount of best settings or flashcard formulation advice is going to save you.

That’s the brutal truth about all of this.